Part I: Introduction to Programming in Python#

In Part I, we will cover the fundamentals of python. Note that this is workshop is not exhaustive, but it will provide you with a useful introduction. There aren many, many, python tutorials, courses, etc. online, so if you are interested in learning more, a quick google search is all you need do.

Most of the output on this webpage is hidden in order to give you the opportunity to think the code through before you click to reveal the output. And remember, press Shift-Enter to run the code.

Follow along in your own blank jupyter notebook or click on the “Live Code/Launch Thebe” button in the upper right corner. It takes a few minutes for the “Live Code” session to launch.

Let’s start with a simple hello world program (just as we did in the video).

Note that # followed by text is a comment. The # sympbol tells python not to interpret this line as code.

# this is a comment

print("Hello World!")

Show code cell output

Hello World!

Note that the syntax matters. What happens if you instead try the following?:

print(Hello World!)

print(“Hello World)

print “Hello World”

print() is one of the built-in functions that are always available when you use Python. Functions are followed by parentheses. Here is a list of all the built-in functions.

To learn more about a particular function, type help()

# information about print()

help(print)

Help on built-in function print in module builtins:

print(...)

print(value, ..., sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

Optional keyword arguments:

file: a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

sep: string inserted between values, default a space.

end: string appended after the last value, default a newline.

flush: whether to forcibly flush the stream.

1. Operations: Python as a calculator#

The above was a demonstration of a simple output. Now, let’s take a look at how to use Python do operations just like a calculator.

+Addition-Subtraction*Multiplication/Division%Modulus**Exponent

# Addition

1+2

Show code cell output

3

Note that:

1+2

3

is the same as

1 + 2

3

Python ignores the white spaces.

# Multiplication

1.6*7.8

Show code cell output

12.48

1.1 Order of Operations#

Just like in high-school arithmetic, the order of operations matters. In Python, the hierarchical order of operations (aka precedence) is as follows:

()Parentheses - Highest Precedence**Exponentiation*Multiplication/Division%Modulo+Addition-Subtraction

Order of operations matter! Try executing 5 + 4 * 16. Before you check the output - which operation will be performed first, based on the list above?

# Order of Operations

5 + 4 * 16

Show code cell output

69

Now, change the above to (5 + 4)*16. Which operation will be performed first? Check the output to confirm.

Parentheses can be used to establish which operation should be performed first.

2. Basic Data Types#

The most common data types in python are:

Integer (1,91,-1923)

Float (1.1, -109.1, 1.00)

Complex (4 + 5j)

String (“name”, “hello”, “123”)

Boolean (True, False)

Let’s take a look these different types. We will start by using the type() function and type type(10). What type do you think 10 is? (Note that type() is one of the built-in Python functions.)

# Display data type

type(10)

Show code cell output

int

What happens if you change the above to type(10.0)? What type do you think this is? Try this yourself by editing the above line of code.

2.1 Type Conversions#

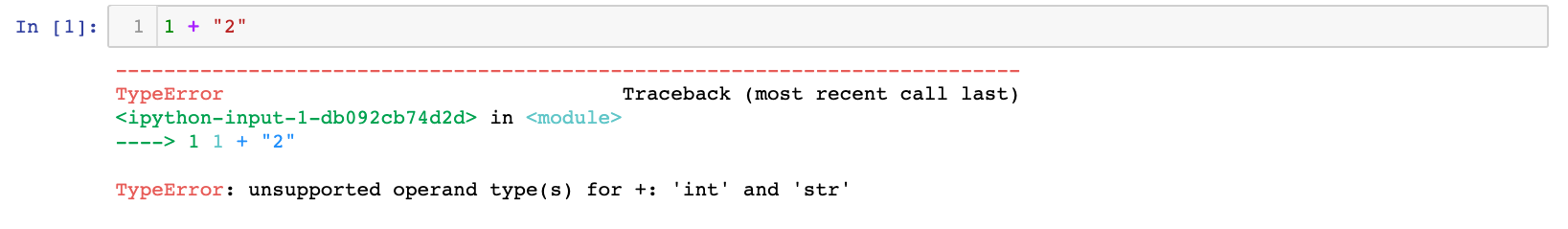

What if I want to add 1 and “2”, where 1 is an integer and “2” is a string? Try typing this on your own. What do you get?

It will result in a TypeError. Some types are incompatible with each other. In this case, you need to do type conversion.

This may seem silly - why would you want to add integers and strings anyway? But, this is actually quite a common issue that comes up.

For example, suppose I entered some numeric measurements in a .csv file but I entered them as text rather than numbers. Then I read this .csv file in Python and try to perform some arthimetic operations. I will get a TypeError. I can avoid editing my .csv file by doing a type conversion within Python.

# Adding an integer and a string using a type conversion

1 + int("2")

Show code cell output

3

int() is another built-in Python function. Other type conversion functions include:

str()float()complex()bool()

3. Variables#

We have seen how we can use Python to perform simple operations, but scientific computing often involves complex computations and big data. We do not want to be constantly typing in numbers - we need a way to store information.

Introducing variables.

# Variables

a = 1 # assign 1 to variable a

b = "hello" # assign "hello" to variable b

c = a + 20 # assign a + 20 to variable c

print(c)

21

Variables must start with a character and can use a combination of characters and numbers (except for the following reserved words).

4. Conditionals: Decision-making in Python#

Learning to write conditionals is the first step in programming. Conditionals allow a program to make a decision (e.g. control output) based on specific information (i.e. the input).

Conditionals in Python follow the follwing format:

if expression1:

command1

elif expression2:

command2

else:

command3

command1will execute ifexpression1is True equivalent.command2will execute ifexpression1is False equivalent, andexpression2is True equivalent.Otherwise

command3will execute.

Note that the colon and the indentation of the commands is an essential part of the syntax.

Let’s try a simple conditional. Which output do you expect to get based on the input?

# A simple conditional example

have_homework = True # assign True to variable have_homework

if have_homework:

print("Time to study!")

else:

print("Time to play!")

Show code cell output

Time to study!

Now edit the above to read: have_homework = False. What output do you get this time?

Also, see what happens if you remove one of the colons or you remove the indentation of the print() commands. You should get an error message - syntax is key!

4.1 Comparators#

Comparison operators (aka comparators) compare the values on either side of them and decide the relation among them. These are often used within conditionals. Comparators will always resolve to a boolean value, i.e True or False.

Here is a list of compartors in python:

>Greater than<Less than>=Greater or equal to<=Less or equal to==Equal!=Not equal

IMPORTANT: Equal comparator is double equal sign, not single.

Here is a simple example.

# Comparator

4 < 5

True

Now try editing the code block above and trying out different comparators.

4.2 Logical Operators#

You can use logical operators to connect multiple expressions. These are also often used within conditionals. Logical operators will always resolve to a boolean value.

and

or

not

Before we dive in, it’s good to note a few properties of booleans:

True and True = True

False and False = False

True and False = False

True or True = True

False or False = False

True or False = True

not is used to reverse the logical state of the operand - i.e., switch True to False and vice versa.

Let’s take a look how these work.

# Logical operators

have_homework = True

need_sleep = True

# try different combinations

need_sleep and have_homework

Show code cell output

True

Try different logical operators by editing the line of code above.

Now let’s take a look at a conditional that contains a comparator and a logical operator. What will the output be?

# A more complex conditional example

have_homework = False

hours_studied = 10

if hours_studied > 4 and not have_homework:

print("Time to play")

else:

print("Time to study")

Show code cell output

Time to play

What will the output be if we make the following changes (independently and all at once)?:

hours_studied = 2have_homework = Trueandtoor

Edit the line of code above to see what happens. Refer to the list of True/False properties above for guidance.

4.3 True / False Equivalent#

Expressions do not have to be strictly True or False for Python conditionals to trigger.

True

Boolean: True

Integer: not 0

String: not empty

False

Boolean: False

Integer: 0

String:

""

Let’s see how this works by looking at another example of conditionals. Take a look at the example and figure out what the output will be, then check your answer.

# Two conditional example

a = 10

b = 20

c = 30

# conditional 1

if a == 10:

print("a is 10")

# conditional 2

if b < a:

print("b is less than a")

elif c and b and a:

print("a,b,c are all True equivalents")

else:

print("nothing happens")

Show code cell output

a is 10

a,b,c are all True equivalents

Now what happens if you make the following changes to the above code block?:

c = 0c = ""b = 2

4.4 Nested Conditionals#

You can also have nested conditional blocks of code. Here is an example:

# A nested conditional

a = 10

b = 20

c = 30

# conditional 1

if a == 10:

print("a is 10")

# conditional 2

if b < a:

print("b is less than a")

elif c and b and a:

print("a,b,c are all True equivalents")

# nested conditional

if c < 40:

print("c is also smaller than 40")

else:

print("nothing happens")

Show code cell output

a is 10

a,b,c are all True equivalents

c is also smaller than 40

Before we proceed to the second part of Module 1, test your new Python knowledge by completing a few short exercises.